(Written by Graham Crozier, 2019)

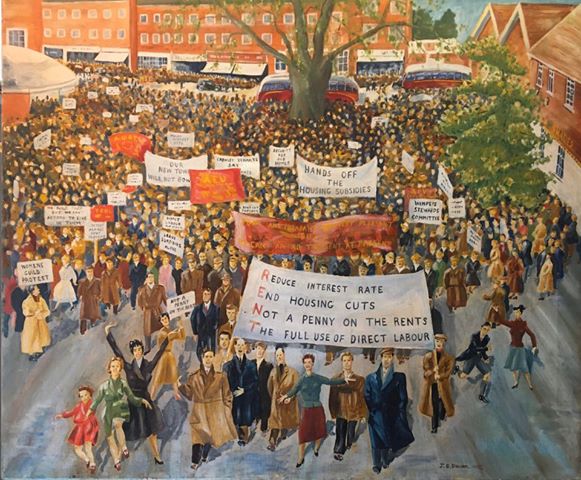

Painted by J.E. Fuller, 1955, Crawley.

90cm x 78cm.

The Rent Strike of October 1955 has all but disappeared from the awareness of people living in Crawley today. However, it can be seen as representing an example of community action in the face of frustration at a perceived lack of progress in the fulfilment of the promise of the New Town project. The actual issue of a rise in the cost of renting from the Crawley Development Corporation (CDC) by two shillings and sixpence per week, was a catalyst for wider concerns about the quality of life in a place seen as lacking the security and stability of the London communities which most of the newcomer population had left.

Concern about housing reflected the insecurities of both the new and existing population. People moved down to Crawley on the understanding that not only was their standard of living going to be much better, but that the costs associated with it were going to be affordable. Early migrants had believed that their rents would be at a fixed level. The actions of both national government and the Development Corporation seemed to be proving them wrong.

This was against a background of a major campaign by the Labour government in the late 1940s to publicise the advantages of moving to one of the New Towns being built around London, in particular the prospect of people having their own, modern home. This, plus the promise of stable employment, was the reason that Crawley’s first ‘settlers’ endured the hardships of poor facilities and the unforgiving clay soil. There was very much a sense that the New Town represented part of the dream of a better, socialised way of life held out by the Attlee government. This, plus the new demographic of the town, accounts for the strong support enjoyed by working-class organisations in Crawley in the 1950s.

However, another factor affecting the issue of housing in the town was that those who lived in Crawley before 1947 could not gain access to new accommodation. The remit of the CDC, the unelected body charged with designing and building the New Town, was to house people moving out of London, not pre-existing residents. This was an obvious source of local resentment, as was the fact that the CDC had the power to compulsorily purchase property and land within the ‘designated area’ that would comprise the heart of the new urban development, including older properties mainly in the High Street. Council housing for those already living in the area remained in the hands of the elected local authorities.

The issue of rents was partially down to the policies of central government. Despite coming to power in 1951 on a programme including investment in house building, the Conservatives moved to remove rent restrictions and security of tenure for council tenants. The physical devastation of the war still being a major issue across the country, Conservative policy was to give encouragement to private construction firms to meet building targets, rather than support local authorities in building social housing.

Rent increases were partly a result of the higher cost of building materials due to shortages of supply. This had an impact on the ability of the CDC to meet its house building targets. By 1952 average rents in Crawley were some six shillings higher than in other local authority areas. Crawley rents were among the highest in the country, with only 5% of authorities charging more. This was at a time when wage levels in Crawley were generally lower than those in London, where rent levels were often capped at pre-war levels.

As an appointed body, answerable to central government and with specific targets to be met, the CDC was very much an instrument for the application of central government policy. Government loans were subject to high interest rates, and the CDC was required to run a balanced budget, with housing income a major source of revenue. This argument for increasing rents did not sit well with the largely left-wing membership of the Crawley Tenants Association (CTA), who argued that housing should be seen as a social service, as much as health and education.

By 1953, the demands being made on working people meant that paying the rent was leaving people with less and less disposable income, with an impact on general standards of living. A newsletter sent out by the CTA portrayed rent increases as a drag on the economic development of the town. Many families were dependent on overtime earnings to make ends meet. This at a time when many firms were forced put their employees on short-time or flat week working due to a general downturn in the economy.

However, it is also the case that the general standard of living of people in Crawley was much higher than they had before moving from London, even before the war, and many were able to benefit from the availability of modern consumer goods, albeit financed through hire purchase.

By mid-1952, Crawley rents were some 50% higher than those for London County Council properties. The fact that many ‘New Towners’ regularly returned to their families in London made the comparison all the starker. However, housing shortages and a lack of jobs in London made a return to their old neighbourhoods impossible for most.

In November, 1952, a Rents Committee was set up by the CTA. This Committee was supported by a wide range of trades unions representing workers on the industrial estate, by the Crawley Trades Council, Crawley Co-operative Women’s Guild, and by the local Labour and Communist parties. The 1950s saw very high trade union membership in Crawley firms; the decade between 1947 and 1957 saw the peak of working-class migration to Crawley, as the infrastructure of the New Town was developing. The CTA was led by Vic Pellen, a local schoolteacher and socialist, and by the Labour parish councillor and local magistrate, Hephzibah Carmen.

The role of the Crawley Branch of the Communist Party in action over local concerns is interesting, because members of the CDC later portrayed the rent strike as the work of outside ‘agitators’ rather than a reflection of the genuine feelings of the local working people.

Crawley Communists saw the ‘displaced’ working class population of the New Town as a promising platform to foster widespread co-operation on issues like rent control. Communist activists were in the forefront of the campaign against rent increases from 1952.

Richard Vines was Convenor of Shop Stewards at APV and also on the Branch Committee of the CP. In an interview with an American academic, Jacob Fried, in 1972 he said that:

‘… people were very concerned that they would not live in Crawley under worse conditions than they had in London … they found mud, no street lights, lack of roadways … trade unions … were deeply committed to action in the community itself … Schools were just not being built and available for the great influx of people … People could express their needs through the Tenants Association … rather than the Labour Party or Communist Party … Neither I nor Alf Pegler (union Convenor at Edwards High Vacuum and not a member of the CP) was officially on it (the CTA) but always our friends were on it, and we could influence it.’

Indeed, the Secretary of the CTA, Joe Sack, was also Secretary of the Crawley CP; David Grove, a CP member who worked for the CDC, made the proposed rent increase known to Vines, Sack and others. This allowed them to prepare to oppose it, including a leafleting campaign that highlighted issues of interest rates, subsidies and building costs, in contrast to the military and colonial spending programmes of the Churchill / Eden Governments.

Concern about the influence of the far left would also undoubtedly have been expressed by Ernest Stanford, who represented the Labour Party on the CDC and was Chairman of Crawley Parish Council. Stanford had helped found Crawley Labour party in 1919. He had been the Labour candidate for the Horsham and Worthing constituency (which included Crawley) in the 1923 and 1924 General Elections. Thereafter, he had been instrumental in getting Communists out of the Labour party after 1925, and had been a staunch supporter of Macdonald as Labour Leader in the National Governments of the 1930s.

However, as a representative of local democratic institutions, Stanford’s voice was probably weak. It is fair to say that the leadership of the CDC was fairly dismissive of the ability of the Parish Council to run any services in the New Town. Fried describes both the County and Parish Councils as ‘timid, unimaginative, and hardly to be considered as equal partners in development’, perhaps a rather harsh judgement although it is certainly true that the demands of the New Town were far beyond anything that local authorities had had to deal with in the past.

In the spring of 1955 central government subsidies to support public sector house building were reduced, resulting in rent rises across the board. Requests to modify these policies fell on deaf ears.

Then, on 17 October 1955, 5,000 Crawley tenants were sent notices to quit by CDC, but with the offer of a new tenancy at higher rents. This unsurprisingly led to protests and demonstrations. A meeting outside the CDC offices in The Tree was broken up by the police. On 26 October, a march through Manor Royal lead to a stoppage on the industrial estate.

A meeting of some 5,000 people in the town centre led to agreement not to pay the rent increases, with the threat to shut down industrial production in some of the towns’ biggest factories, such as APV. Richard Vines told Fried:

‘At APV we decided to have a work stoppage on a certain day as a protest … APVs marching past factories, all the other workers trooped out to join us in the march – along with the building workers from construction sites … it was a marvellous thing to see the whole of the people march into the square in their working clothes protesting the rent increase.’

The protestors carried banners that encapsulated their grievances, including: ‘Hands off Housing Subsidies’, ‘We build them but we can’t afford to live in them’ and ‘Port and Pheasant are very Pleasant but We Can’t Afford the Rent at Present.’

Some of the participants may have remembered rent protests in London before the war, such as the 1938-39 Stepney rent strike, which was never resolved due to the outbreak of war; the sense of excitement in collective working-class action is palpable in Vines’ recollection of the event.

Reaction to the rent strike clearly reflected the political interests of the groups involved. Robert May (General Works Manager at APV during the strike and first chairman of Crawley Urban District Council on its formation in 1956), told Jacob Fried that:

“It went on for a few weeks and it was the women who paid up, in the end. They feared being turfed out, to lose their homes. So it was the women who undermined the Rent Strike. The men did not know and were militant.”

It should be noted that workers at APV were amongst the more militant supporters of the rent strike. May was certainly concerned enough about the loss of productivity at the firm to be included in the deputation to the CDC.

Again, interviewed in 1972, Robin Clarke, assistant to Col. CAC Turner, General Manager of the CDC, saw the strike very much in political terms; for him the strike represented a struggle between the CTA on the left and the CDC on the right:

“…the Development Corporation was not a democratic organisation and there was no elected representative the tenants could go to complain … we could not be got at … The Corporation did not react to these pressures but only held its ground … just played it cool … After this, the Tenants Association faded away… We did not lose our nerve over all the fuss.”

As chair of the CDC, Thomas Bennett conducted most of the meetings with the CTA representatives. He held to the line that the rent increases were to remain, and that they were even fair. It should be noted that as a New Town, Crawley was given a higher central government housing subsidy than that given for local authority housing elsewhere. In Bennett’s interviews with Fried, he hardly mentions the role of the Tenants Association or the strength of local support for the strike, instead placing the blame on outside ‘agitators’.

The strike gradually weakened, from a highpoint of non-payment of 58% in the first week. It is clear that the non-representative nature of the CDC was an asset in adopting a hard-line position, with central government, along with rising costs, being held to blame for rent increases.

By the mid-1950s, central government policy had turned its attention to the costs of slum clearance and urban regeneration nationally, which resulted in a reduction in the subsidy for general house building. In a statement to the House of Commons in November, 1955, the Minister of Housing, Duncan Sandys, an aggressive free-marketeer, made it clear that using subsidies to keeping down rent levels was not possible, and indeed was seen as unfair to general taxpayers and ratepayers.

Sandys said he recognised that the New Towns were a special case when it came to subsidies because of the lack of low-cost pre-war housing that could be used to bring down the overall levels of rent.

Frederick Gough, the Conservative Member for the Horsham constituency, which included Crawley, praised the CDC for the progress it had made in building new homes in Crawley, and highlighted the fact that the majority of the New Town population were ex-Londoners: ‘We have gone nearly two-thirds of the way to completing our plans, but the new people who are coming to us may upset these plans … Is a new town to be deprived of that sort of help (subsidies) and assistance because it is managed, not by a local authority, but by a corporation?’ (This was clearly seen as a rhetorical question, as no reply was given by the Minister!). Gough had previously attacked the CTA for its ‘left-wing bias’.

In his annual address in April 1956, Thomas Bennett stated that the rent rises were ‘the lowest amount which would permit the Corporation to carry out its obligation of producing a balanced housing account.’

Richard Vines, unsurprisingly, saw the consequences of the strike from a different viewpoint:

‘It changed the Government’s outlook on New Town housing and from then onward they went to privately-built houses and this tended to rub out what the towns were built for – to accommodate by rental housing the working people … Now the split began between house-owners and renters.’

In the end, the Rent Strike did not achieve its main goal of keeping rents low. By Christmas 1955 77% tenants were paying the higher rent. By February 1956 everyone had moved on to the new rents. However, a three-year rent freeze had been agreed. Ultimately, the strike failed due to tenants’ fear of losing their homes rather than the claims of the CDC that rent increases were seen as reasonable by the majority of people.

The debate about the place of publicly-owned housing in socially equitable communities continues, while thousands across the country still live in high-cost, low quality private accommodation.

Sources:

Fried, J. (1972) ‘People and Events that Shaped Crawley’. Crawley Council for Social Services.

Fried, J. (n.d.) ‘Crawley New Town – Leadership and Community Formation in a Planned Community.’ Hopi Press.

Gray, F. ed. (1983) ‘Crawley, Old Town, New Town’. Centre for Continuing Education, University of Sussex. Occasional Paper No. 18.

Green, J & Allen, P. (1993) ‘Crawley New Town in Old Photographs’. Alan Sutton Pub. Ltd. (see chapter 4 for photographs of the strike demonstrations)

Osborn, F & Whittick, A. (1963) ‘The New Towns. The Answer to Megalopolis’. Leonard Hill Ltd.

Debate on Housing Subsidies Bill. Hansard HC Debate 17 November 1955. (Vol 546 cc 791-899).